The beginning in grief

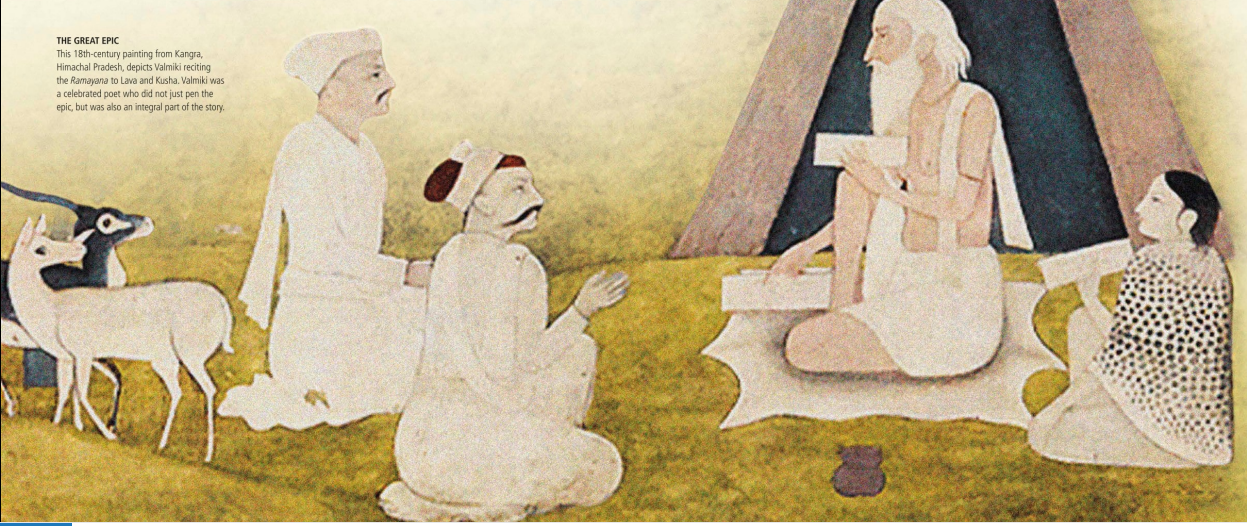

The Ramayana is an ancient Indian epic that narrates the life of Prince Rama, his wife Sita, and his loyal companion Hanuman. It is attributed to the sage Valmiki and is written in Sanskrit. The story is divided into seven Kandas (books) and consists of about 24,000 verses.

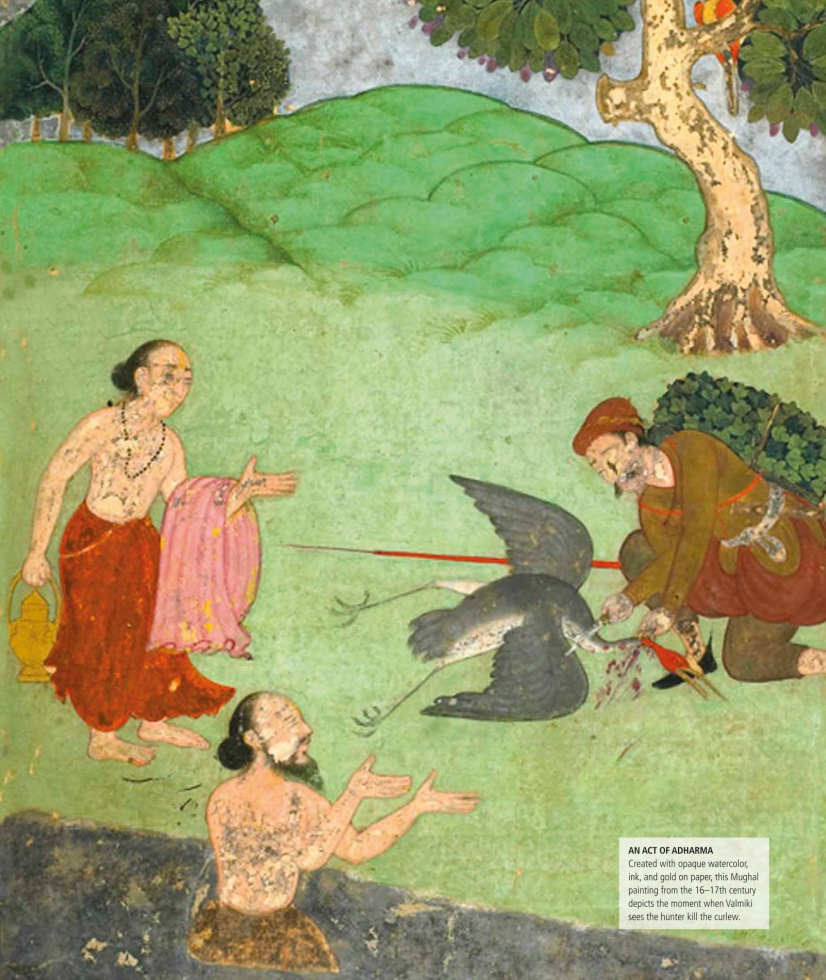

As with majority of the epics both in Indian and western traditions, the epic starts with an event of excruciating grief. The sage Valmiki witnesses a hunter kill one of a pair of mating krauncha birds (a type of curlew or sarus crane). Seeing the surviving bird’s grief, Valmiki is overcome with compassion and spontaneously utters a curse in metrical verse:

“Mā niṣāda pratiṣṭhāṁ tvam agamaḥ śāśvatīḥ samāḥ

yat krauñca-mithunād ekam avadhīḥ kāma-mohitam”

(Meaning: “O hunter, may you never find peace for eternity, as you have killed one of this pair of krauncha birds while it was overcome with love.”)

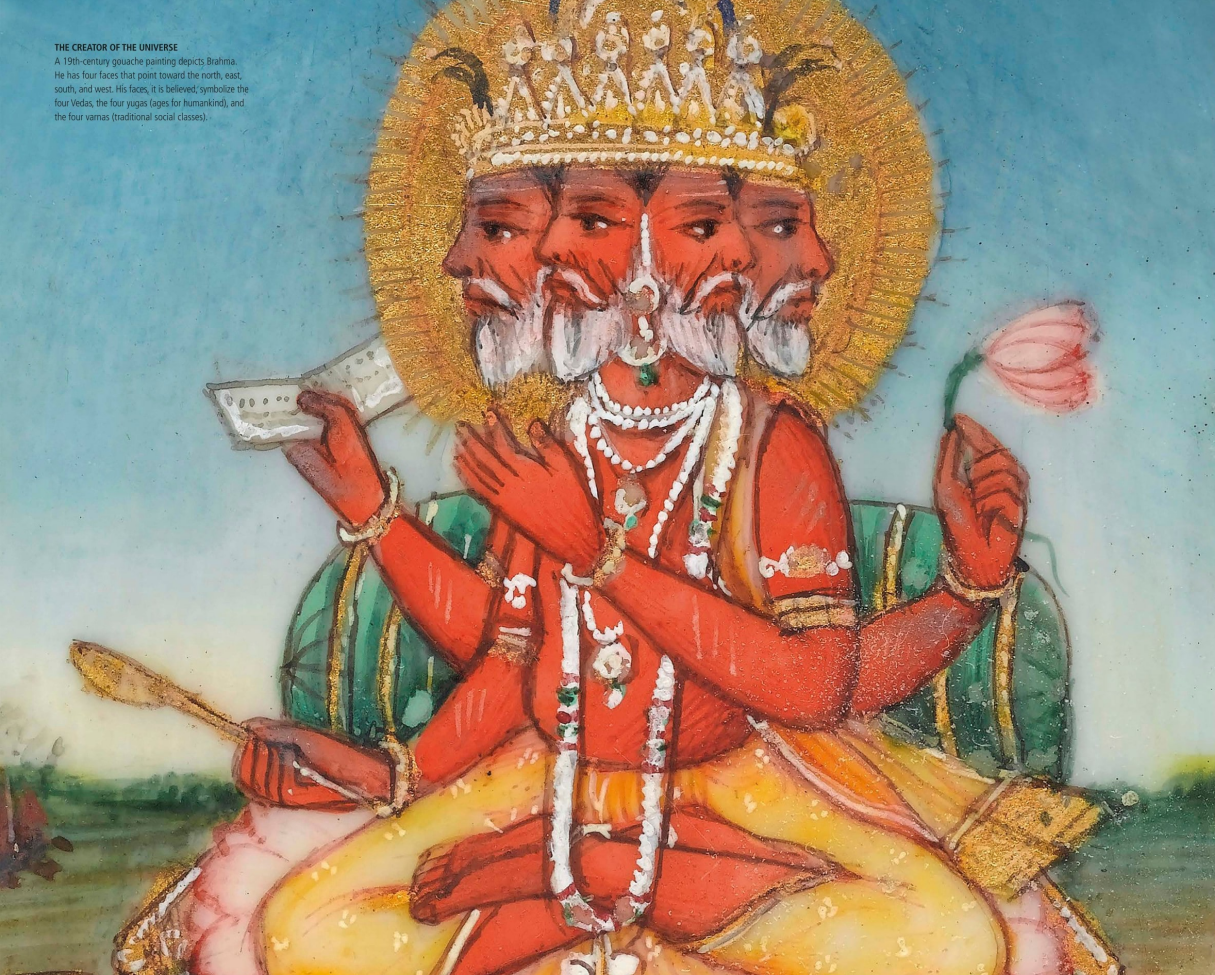

This is considered the first shloka (metrical verse) in Sanskrit poetry. Inspired by this, Brahma later commands Valmiki to compose the Ramayana in the same poetic form. So, in a way, the epic is born out of grief and compassion.

This theme of grief, loss, and emotional turmoil as a catalyst for epic storytelling is quite common in Hindu epics. Many great Hindu scriptures and poems begin with a moment of deep sorrow, injustice, or cosmic imbalance, which then sets the stage for the unfolding narrative. Here are some key examples:

1️⃣ Ramayana – Born from Valmiki’s grief

As you pointed out, the Ramayana begins with Valmiki’s sorrow after witnessing the killing of the krauncha bird. This grief transforms into poetic inspiration, leading to the composition of the epic.

2️⃣ Mahabharata – Vyasa’s sorrow over a fractured lineage

The Mahabharata is traditionally attributed to Sage Vyasa, who composes it out of his own grief over the tragic decline of the Kuru dynasty.

The story itself begins with the lamentation of the blind king Dhritarashtra, who grieves the destruction of his sons (the Kauravas) in the Kurukshetra war.

The Bhagavad Gita, embedded within the Mahabharata, also begins with Arjuna’s despair on the battlefield, which leads to Krishna’s divine discourse.

3️⃣ Bhagavata Purana – Sorrow of Parikshit

The Bhagavata Purana (which narrates the life of Krishna and other divine stories) is initiated when King Parikshit is cursed to die in seven days. Out of grief and a quest for knowledge, he listens to the sage Shuka, who narrates the Purana.

4️⃣ Shiva Purana & Linga Purana – Sati’s grief and self-immolation

The story of Sati’s self-immolation due to her father’s insult to Shiva leads to cosmic upheaval. Her grief becomes a pivotal moment that reshapes divine and cosmic order.

5️⃣ Devi Mahatmyam (Durga Saptashati) – Gods’ lamentation over Adharma

This text begins with the Devas lamenting their helplessness under the oppression of Mahishasura. Their sorrow leads to the manifestation of Goddess Durga.

The Deeper Pattern

In Hindu thought, grief is often the seed of wisdom, transformation, and divine intervention.

The cycle of destruction and renewal is central to these narratives—what begins in sorrow often ends in dharma being restored and a higher truth being realized.

So yes, the pattern you noticed in the Ramayana holds true across many Hindu epics. It’s almost as if grief is the fire that forges wisdom, poetry, and divine action.

The ethos of surrender and divine intervention

It is interesting to note that the entire episode of the killing of the curlew and the subsequent curse is shown as something that happens spontaneously, without the active intervention of Valmiki. The entire episode is so overwhelming to him that by itself the shloka of the curse comes out of his mouth, and he is astonished to find that he has uttered the sholka, and that he was so merciless towards the hunter. He has a mixed feelings of grief as well as compassion for both the curlew and the hunter, to some extent. But then the curse actually comes out, and that too comes out in a beauty of poetry in right metres. Valmiki wonders about the significance of the shloka, and sits for meditation.

It is then Brahma himself appears, and proclaims that he had willed the shloka to be created in the right metre and be uttered by Valmiki. He instructs Valmiki to use this shloka and its metre to further develop it and integrate the story of Rama’s life in this same form.

Rasas, Aesthetics and Bhavas

The Ramayana is not just a story; it is a complex tapestry of emotions, aesthetics, and spiritual teachings. The epic employs various rasas (aesthetic flavors) and bhavas (emotional states) to evoke deep feelings in the reader or listener.

1️⃣ Rasa: The Ramayana is rich in various rasas, such as śṛṅgāra (love), vīra (heroism), karuṇa (compassion), and bhayānaka (fear). Each character and event evokes different rasas, creating a multi-layered emotional experience.

2️⃣ Bhava: The bhavas in the Ramayana range from śanta (peace) to udvega (anxiety). For example, Sita’s abduction evokes karuṇa, while Rama’s valor evokes vīra.

3️⃣ Rasa and Bhava Interaction: The interplay between rasa and bhava is crucial. For instance, the śṛṅgāra rasa in Rama and Sita’s love story is often tinged with karuṇa due to their trials and tribulations.

4️⃣ Aesthetic Experience: The Ramayana’s poetic form, rich imagery, and emotional depth create a profound aesthetic experience. The reader is not just a passive observer but is drawn into the emotional landscape of the characters.

The story of Ramayana as instructed by Brahma is not written in a book. Rather it is sung by Luv and Kush in the same metre as was instructed and willed by Brahma.

Want of the son

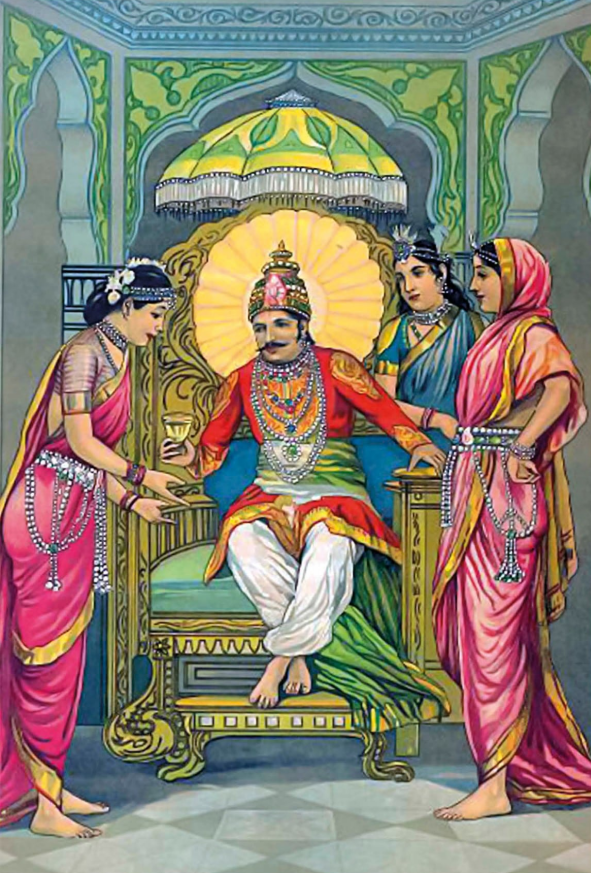

As if one grief is not enough, the Ramayana is set forth on another grift. This time the grief of Dasharatha, the father of Rama, who is childless and wants a son. To fulfill his wish, he performs the Ashvamegha Yajna. As Dashratha performed the rituals, a resplendent figure emerged from the holy fire, holding a celestial dish made of molten gold. He was as tall as a mountain, and blazed like the Sun. He gave the king a bowl of payasam (a sweet dish made of milk and rice) and instructed him to give it to his wives, Kausalya, Kaikeyi, and Sumitra.

(An oleograph by Raja Ravi Verma, of the scene of Dasharatha offering the payasam to his three wives.)

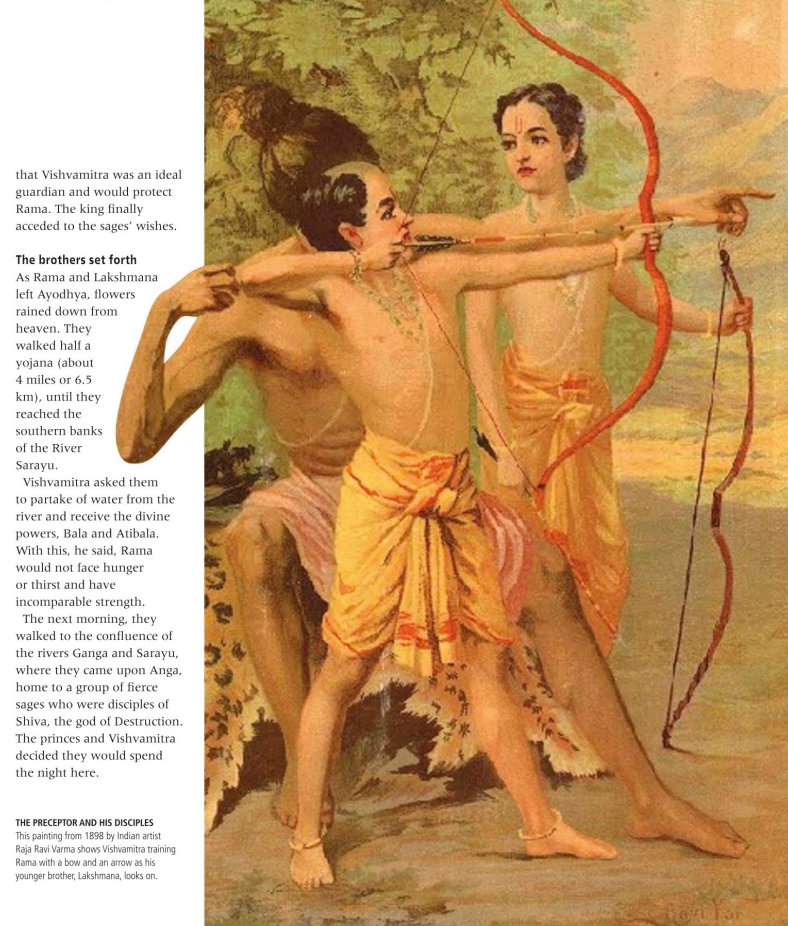

Vishvamitra’s request

Rama is just 16 years old and he is asked by Vishvamitra to accompany him to the forest to protect his Yajna from the demons! Dasharatha is not willing to send Rama to the forest, but Vishvamitra convinces him. This is another scene of grief and parting that is very poignant in the beginning of the epic.