Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) was born into an Anglo-Irish family in Dublin, and he grew up there, going to Trinity College Dublin and then Oxford for university, before moving permanently to England in 1878. He wrote many plays, including The Importance of Being Earnest and An Ideal Husband. He was imprisoned and sentenced to two years of hard labour, which began in May 1895 (he wrote De Profundis and The Ballad of Reading Gaol in light of this).

The reason for his imprisonment came from an act of revenge. Wilde himself had issued civil proceedings against John Solton Douglas (proceedings that Wilde later dropped), but during the trial, it came to light that Bosie Douglas (the son of John Solton Douglas) was Wilde’s lover. Wilde’s harsh punishment was as a result of anti-homosexuality laws. On his release from prison in 1897, he set sail for France, never to return to England, where he lived in dejection and poverty. He died less than three years at the age of 46, and he is buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

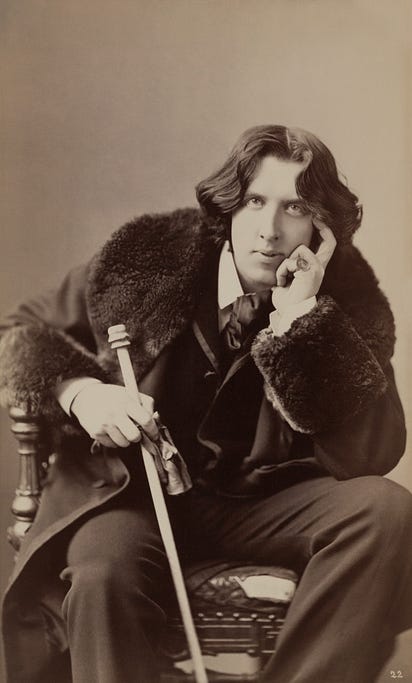

Oscar Wilde. Photo by Napoleon Sarony. This work is in the public domain in the US because it was published (or registered with the US Copyright Office) before January 1, 1930.

While in jail, he wrote De Profundis. Ostensibly a long letter to his lover, alongside a defence, it also contains meditations on religion, language, aesthetics, and learning. He was given only a single sheet of paper a week, which he covered closely with handwriting. Each sheet was taken away from him after it was full, and when — the next week — he was given another sheet of paper, he continued from where he’d left off. De Profundis was published posthumously in 1905.

The title of his work — De Profundis is Latin for “out of the depths” — was taken from the opening lines of the 130th Psalm: “Out of the depths I cry to you, Oh Lord.”

The below sonnet, which was published in 1881, demonstrates Wilde’s lifelong interest in, and also critiques of, religion. The rejection of “terrors of red flame and thundering” in favour of lilies, olive groves, doves, autumn afternoons, fields, the song of the gleaner, and “the splendid fulness of the moon” demonstrate his disposition of love and devotion to the world — and the world’s maker — rather than to the strictures of power. In my opinion, “I think it is of Thee the sparrows sing” is one of his most beautiful lines.

Sonnet On Hearing the Dies Irae Sung in the Sistine Chapel

Nay, Lord, not thus! white lilies in the spring,

Sad olive-groves, or silver-breasted dove,

Teach me more clearly of Thy life and love

Than terrors of red flame and thundering.

The hillside vines dear memories of Thee bring:

A bird at evening flying to its nest

Tells me of One who had no place of rest:

I think it is of Thee the sparrows sing.

Come rather on some autumn afternoon,

When red and brown are burnished on the leaves,

And the fields echo to the gleaner’s song,

Come when the splendid fulness of the moon

Looks down upon the rows of golden sheaves,

And reap Thy harvest: we have waited long.

By Oscar Wilde, from the 1881 pamphlet Poems. This work is in the public domain, and all of Wilde’s poems can be found at the Project Gutenberg website.

question:

Oscar Wilde begins his sonnet with the words “Nay, Lord ….” as he directs attention away from institution and towards the landscape. Has there been a time when your attention was directed away — intentionally or unintentionally — from one thing toward another, more sustaining thing?